EDIT 10.06.2022: Hi, I’m from the future, UPM is mature now! You can also use this tool as a package, here. I also solved an emberassing bug present in the previous version,

EDIT 10.11.2020: You can find a sample project containing everything in this post here.

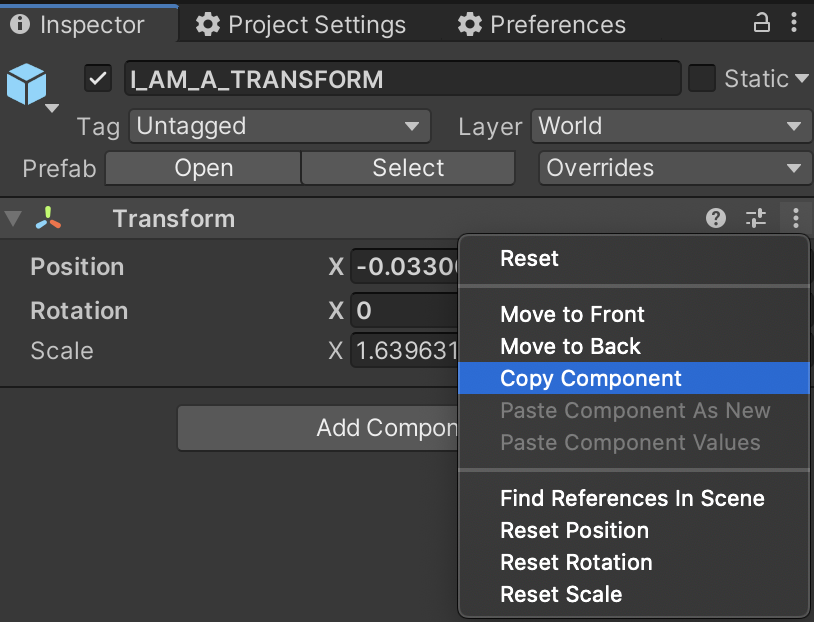

We all know the ol’ trick of accessing the little ‘cog’ above the transform, which allows you to copy a default serialization of a components’ value, and paste it.

But what will you do with a hierarchy that is a bit more… complex?

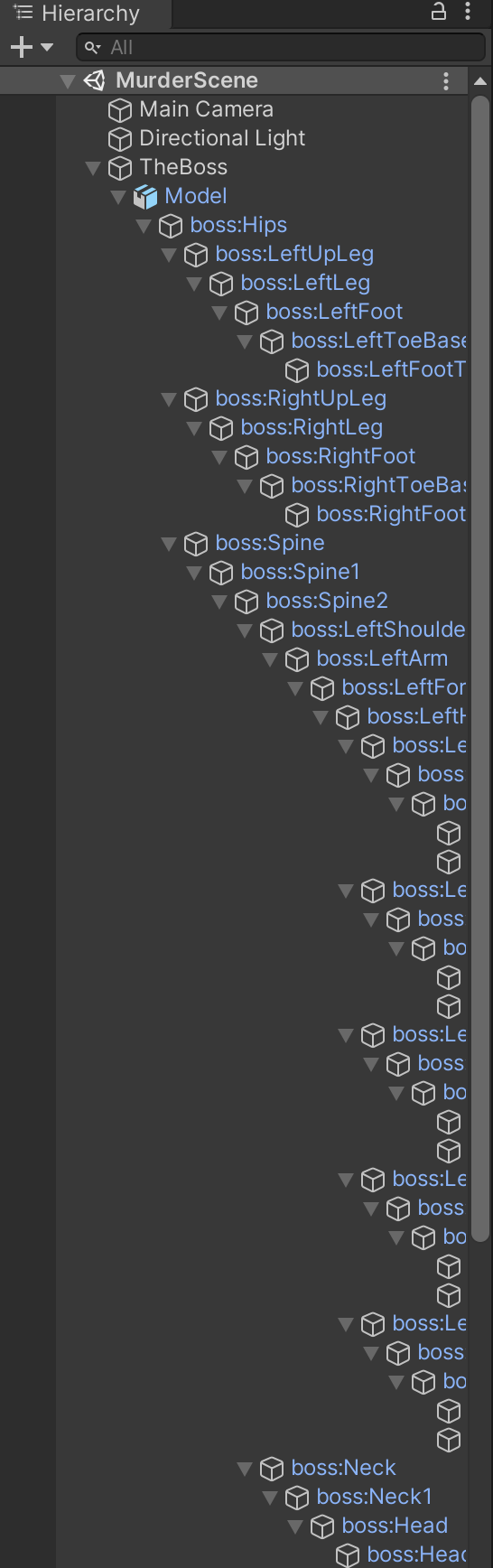

Recently I’ve worked on a game with amazing character models. They were very rich in hierarchy, and had multiple animation sets. Their FBXs were big, so we wanted to use the same FBXs for different scene with the characters.

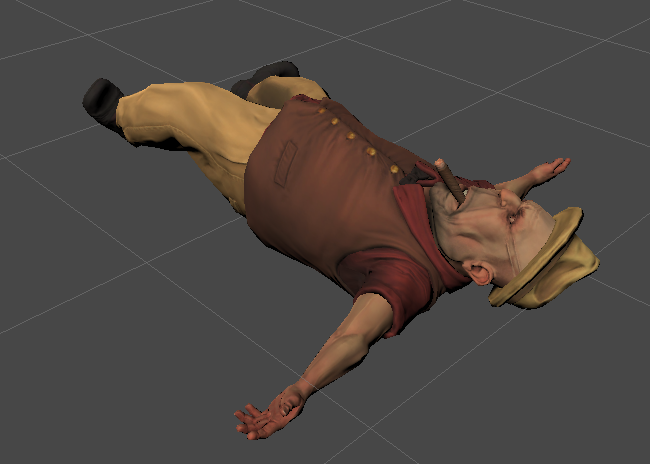

Since I can’t use the original model, I’ll use my go-to victim, The Boss model from Mixamo

Let’s say I want to position the model in a specific scene, ‘frozen’ on this animation’s last frame.

Poor boss. They found him like this in the back alley…

Since the hierarchy is complex, I can’t use my trusty clipboard and the ‘trick’ I’ve mentioned above. I’m not going to individualy move the model to fit this! Especially if I use external models and animations and want to develop rapidly.

Let’s introduce Scriptable Objects (in case you haven’t met them yet) and how they can help us in this, and later implement a simple MonoBehaviour that will allow us to capture the model’s transforms into that scriptable object. And, finally, we’ll implement a load method that’ll read from the scriptable object and place the character just as it was in run mode.

Scriptable Objects - a short introduction

In case you already what these are, by all means, jump to the implementation section.

I highly suggest reading up on Unity Docs, but this is the TL;DR version:

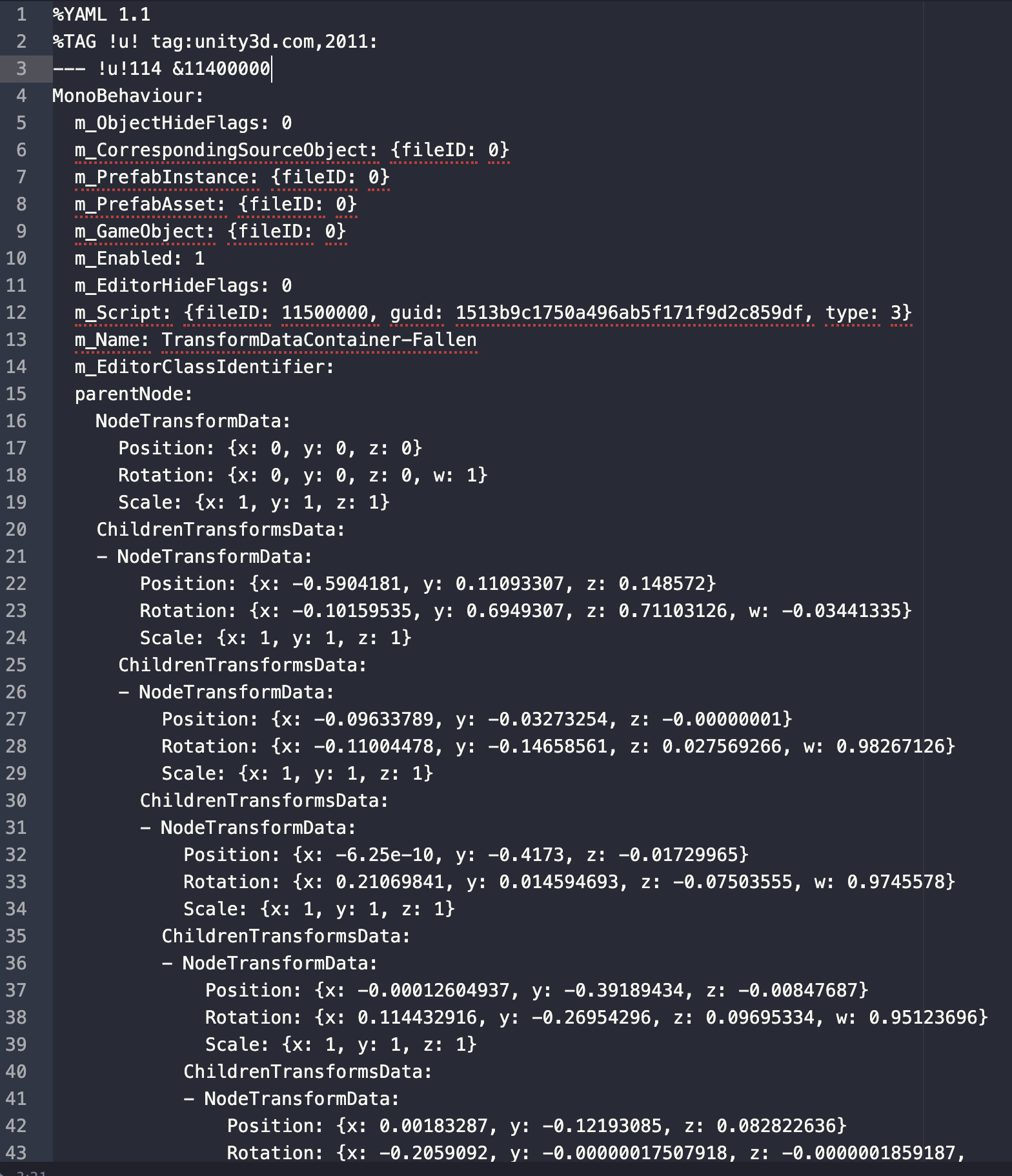

Scriptable Objects are a tool to share data between different classes, but very useful bi-product of that is that this data is serialized (specifically, stored as strings in a YAML file) and persisted between play sessions. I often use this for configurations, player data like score, and other hacks.

Here is an example file:

Why would someone use indentation-based formatting like YAML? or indentation-basd programming languages….? I digress. Let’s write some C#!

Scriptable Objects - implementation

This is how our ScriptableObject, called TransformDataContainer.cs, will look like:

using UnityEngine;

[CreateAssetMenu(fileName = "TransformDataContainer", menuName = "ScriptableObjects/TransformDataContainer")]

public class TransformDataContainer : ScriptableObject

{

public TransformNode parentNode;

}

Of course, TransformNode is a custom class I’ve used to obfuscate a transform. This will allow a tree scrutcure recursion later on. Just notice that helper attribute that enables Unity to create those objects from the editor and not just through code.

this is TransformNode.cs:

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

[Serializable]

public class TransformNode

{

public TransformData NodeTransformData;

public List<TransformNode> ChildrenTransformsData;

}

Again quite simple. Each transform has data for it’s GameObject, and his children’s Nodes reference. Notice it has the Serializable attribute, since it is meant to be a part of a scriptable object.

And finally, this is TransformData.cs:

using System;

using UnityEngine;

[Serializable]

public class TransformData

{

public Vector3 Position;

public Quaternion Rotation;

public Vector3 Scale;

}

Here you might raise your brow. Why can’t I just keep a reference to the Transform? This is because Unity’s Transform is not Serializable. We have to keep it down to basic serializable types or structs to enjoy storage-persistance. References are not serialized (Unity does serialize references between components and gameobjects through .meta files, but I will not cover this here).

Ok, we have our model. Now let’s implement the logic.

Implementing the ‘record’ of our TransformRecorder

So we’ve established that our ‘clipboard’ will be a scriptable object. From now on It’s actually quite simple. We’ll traverse the entire transform’s hierarchy recursively, top-down, and persist the properties that interest us into the scriptable object.

If you have no idea what recursion means, you have a deeper knowledge gap that needs to be filled. I recommend searching online for tutorials like this or this. Implement some fibonacci series functions!

So how does TransformRecorder.cs looks?

public class TransformRecorder : MonoBehaviour

{

[SerializeField] private TransformDataContainer _transformDataContainer;

[Button]

public void RecordTransforms()

{

if (_transformDataContainer != null)

{

_transformDataContainer.parentNode = RecordTransformsRecursively(transform);

}

}

private TransformNode RecordTransformsRecursively(Transform parent)

{

var directChildren = GetDirectChildrenOfTransform(parent);

var nodeData = new TransformNode

{

NodeTransformData = new TransformData

{

Position = parent.localPosition,

Rotation = parent.localRotation,

Scale = parent.localScale

}

};

if (directChildren.Count > 0)

{

nodeData.ChildrenTransformsData = new List<TransformNode>();

foreach (var child in directChildren)

{

nodeData.ChildrenTransformsData.Add(RecordTransformsRecursively(child));

}

}

else

{

nodeData.ChildrenTransformsData = null;

}

return nodeData;

}

private List<Transform> GetDirectChildrenOfTransform(Transform parent)

{

var directChildren = new List<Transform>();

foreach (Transform directChild in parent)

{

directChildren.Add(directChild);

}

return directChildren;

}

}

This is a bit overwhelming at first glance. A few notes that’ll explain everything:

- The recursion step is done on RecordTransformsRecursively.

- Why do we need the GetDirectChildrenOfTransform method? Because gameobject.GetComponentInChildren<> will flatten the bottom hierarchy, making it impossible to keep the structure. Fortunately, Transform implements a generator function that will return only the direct children with foreach, as an enumerable. This bit of the code can be optimized for truly huge game objects, but as a general rule I prefer readability in editor tools I know I won’t use in runtime, and not very often.

A note on [Button]s

I’m using the excellent, excellent Odin Inspector plugin for editor tools, both at work and at home. The [Button] attribute, which is derived from their plugin, does just that - exposes the method as a button. In case you haven’t spend the very cost-effective 55$ purchase of the plugin don’t hesitate and just remove the [Button] attribute and add this file instead to get the same buttons (TransformsRecorderEditor.cs).

using UnityEditor;

using UnityEngine;

[CustomEditor(typeof(TransformRecorder))]

public class TransformsRecorderEditor : Editor

{

public override void OnInspectorGUI()

{

if (GUILayout.Button("Record Transforms", EditorStyles.miniButton))

{

((TransformRecorder)target).RecordTransforms();

}

if (GUILayout.Button("Load Transforms", EditorStyles.miniButton))

{

((TransformRecorder)target).LoadTransforms();

}

DrawDefaultInspector ();

}

}

Easy does it. I highly suggest tinkering around with the UnityEditor namespace, suffer through, and understand why forking 55$ to Sirenix isn’t that bad.

## Implementing the ‘load’ of our TransformRecorder After implementing the record, this is way easier. Add these to the TransformRecorder.cs file:

[Button]

public void LoadTransforms()

{

if (_transformDataContainer != null)

{

LoadTransformsRecursively(transform, _transformDataContainer.parentNode);

}

}

private void LoadTransformsRecursively(Transform parent, TransformNode nodeNode)

{

var directChildren = GetDirectChildrenOfTransform(parent);

if (directChildren.Count > 0)

{

for (int nodeIndex = 0; nodeIndex < nodeNode.ChildrenTransformsData.Count; nodeIndex++)

{

LoadTransformsRecursively(directChildren[nodeIndex], nodeNode.ChildrenTransformsData[nodeIndex]);

}

}

parent.localPosition = nodeNode.NodeTransformData.Position;

parent.localRotation = nodeNode.NodeTransformData.Rotation;

parent.localScale = nodeNode.NodeTransformData.Scale;

}

Pay <3 - the order is reversed, since we want to set these properties, and specifically the scale property, in a bottom-up manner.

## Hooking it all together So now we have our new MonoBehaviour. Supposing everything compiles, the ‘recipe’ from here is:

- Add TransformRecorder.cs as a componenet to your model

- Create a new ScriptableObject for the transform. In case you forgot, creating the ScriptableObject is done by right clicking on the desired path on the Project Window, and going through Create -> ScriptableObject -> TransformDataContainer.

- Reference the new scriptable object within the TransformRecorder.cs component

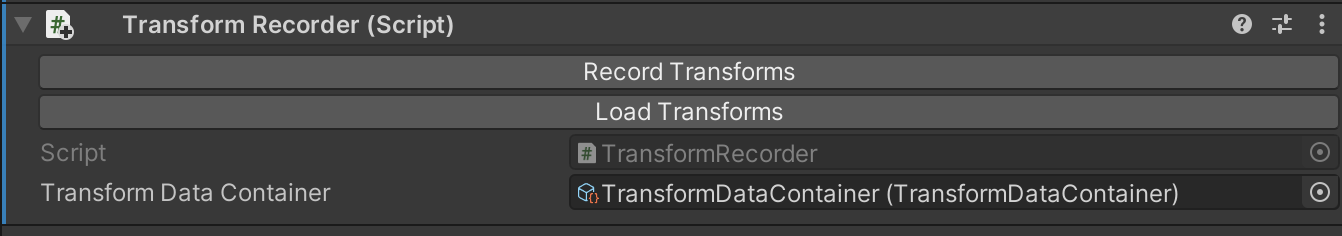

Your componenet should look like this:

- Run the game

- Press the ‘Record Transforms’ button on the component

- Stop the game

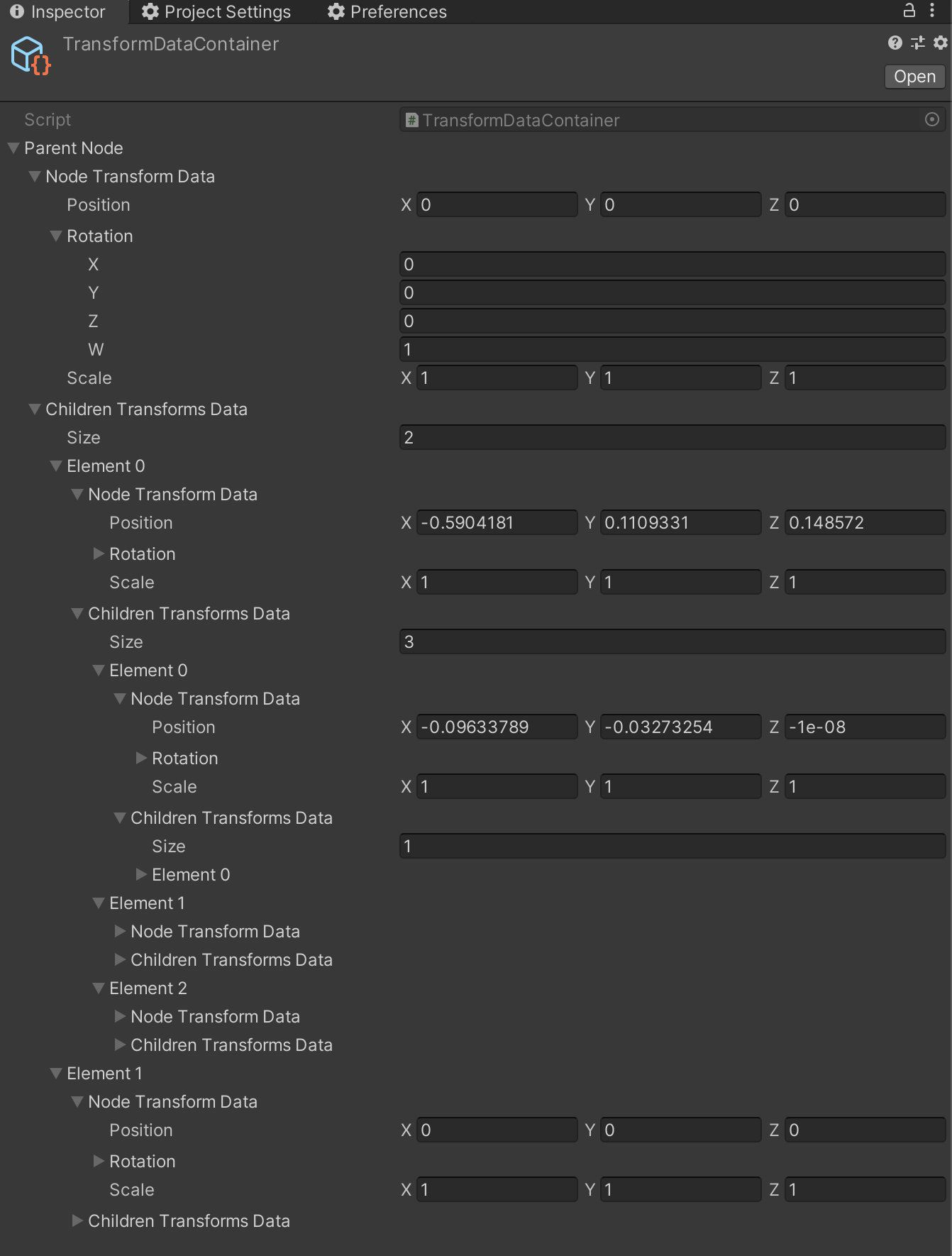

Your scriptable object should contain the hierarchy now:

- Press ‘Load Transforms’ on the component

Done!

Further expansion of this component

- You don’t have to necessarily record Transforms. I can see this easily used for stateful scripts. Maybe you want to capture a level’s state to save it? Or maybe you need to capture the active-state of gameobjects in a certain situation in your game for debugging?

- You can create ‘presets’ of the animations with multiple Transform objects (including the T-Pose), and cycle through them as necessary.

TODO

publish the sample project on github and link from this postyou can find it here- create scriptable object assets dynamically for each recorded object

- create a unity package for project

- public on the unity assets store